|

If you thought that after 10 years of research you would know everything about your ancestors, then you might be in for a big surprise. This happened to me after receiving an email from a certain Dr. J.J.P. de Jong. Dr. de Jong is a researcher of East Indian and Chinese families in the nineteenth century. Specifically his research is centered around families who had been active in startups of new enterprises, tea and coffee plantations, sugar manufacturing etc.

He discovered that the tea company Sinagar in the Preanger area (known by the famous book of Hella Haase: Tea lords) was possibly started by my ancestors from the Tan family. Dr. De Jong emphasized that his source was reliable, viz an official study of the governments cultures from 1869 based on official documents. Since he had difficulty in finding all the names in my family tree on internet: www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-kan-han-en-tan/ he contacted me by E-mail.

It turns out that difficulties arose due to different ways of transcribing Chinese names, and respectively failures in writing correct names in official administrative documents. So I was suddenly confronted with questions about a tea company in our family of which I never had heard of before.

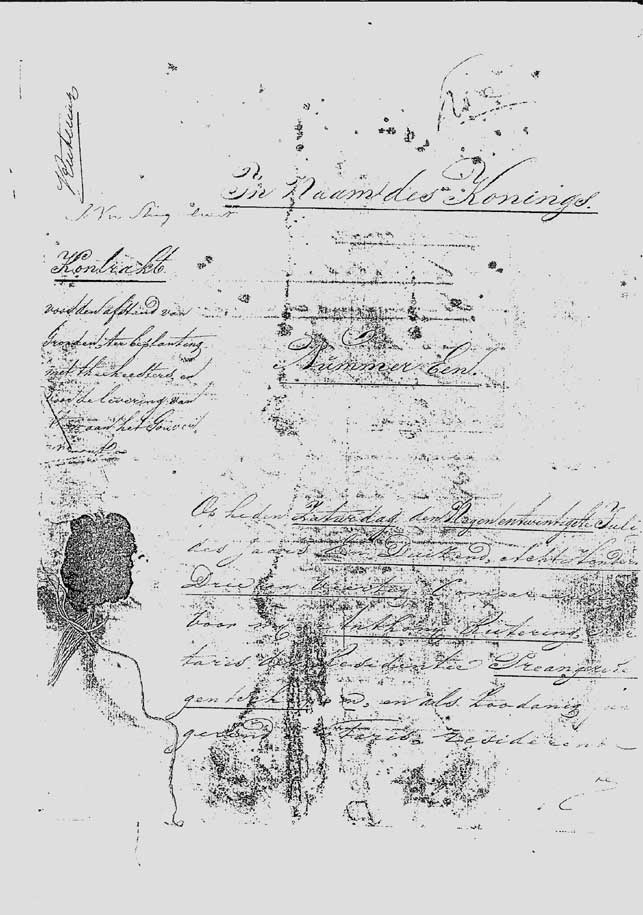

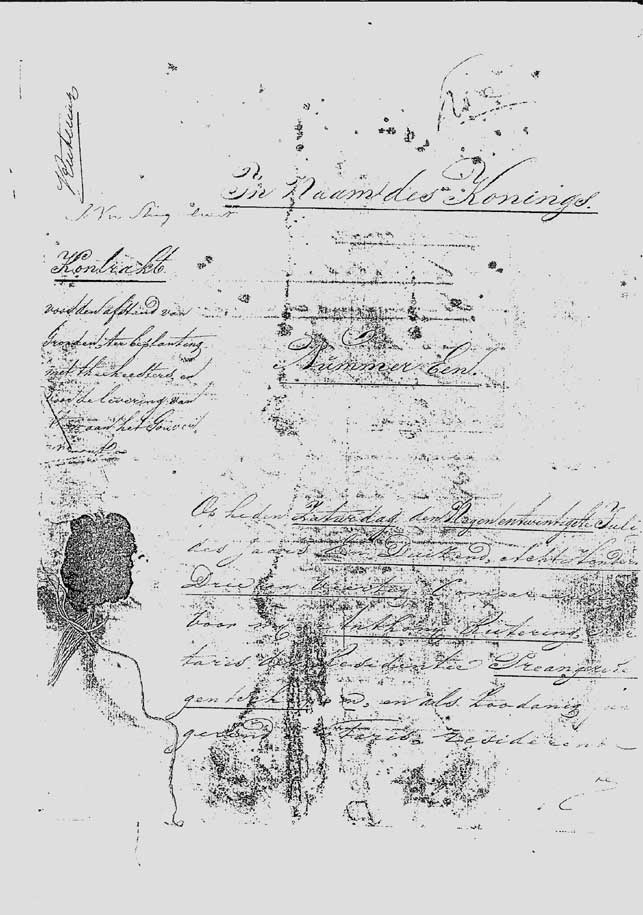

Enquiries by our eldest living cousin of the Tan family: Tan Eng Swie yielded a surprising clue. It happened that Tan Eng Swie possessed a photocopy of a contract, and since he could not read the old handwriting, he had never read through the contract. Because Ems by her search of her own family tree, could read old Dutch script handwriting, she typed out the entire contract.

Now we could read the contract and it appeared to be a tea contract dated 29 July 1843. It turns out that Dr. De Jong, who did not know of this particular tea contract, just offered the right information drawn from those official documents. The tea contract was part of the concessions emitted by the East Indian government as part of the Cultuurstelsel. It was a shock to me to realize that my ancestors have been involved in the Cultuurstelsel.

This Cultuurstelsel was introduced in 1830 under Governor General van den Bosch by the Dutch government in their colony East Indies. Part of the agricultural area cultivated by the locals had to be reserved for the harvest of products which could be exported. In Indonesia nowadays this is taught at school as “Tanam Terpaksa” (forced agriculture) because the local people were compelled to plant Cultuurstelsel crops on the best part of their property. This resulted in that little land and time was left for growing food, causing famine under the population.

Tea plants were among the products which should be grown on the plantations of the colonial government. That is why already in 1827 about 13000-17000 tea plants successfully were grown in ’s Lands Plantentuin (Botanical Garden) in Buitenzorg. These plants were cuttings from the original plants which were imported by Von Siebold and Jakobson and planted by de Serriere with the aid of Chinese planters. Therefore tea could be tasted at the first Colonial Industrial Exhibition of August 24, 1828.

For the first tea plantations in the Preanger area the locations Bodjanegara, Tjioemboeloeit, Radjamandala and Tjikadjang were chosen [/2/, p.149]. In 1842 the colonial government decided to emit 3 new contracts for private exploration on the locations Sinagar, Perakansalak and Djatinangor. The area of the estates was 300 bouw (or 0,21 km2; 1 bouw = 7.096,50 m2).

The search for missing puzzle pieces.

|

With this tea contract Tan Soeij Tiang gained the right to cultivate tea for the Dutch East Indian Government and to sell tea at a prefixed price and quality. The tea was to be cultivated on the land Sinagar, close to the city of Tjiandjoer, property of the Government, and leased for free to Tan Soeij Tiang for this purpose. The contract was to last 20 years.

Tan Soeij Tiang is the younger brother of my great great grandfather Tan Soeij Tjoe.

Tan Soeij Tjoe (1808 -1850) signed the contract as one of the two individual fellow debtors.

The fact that Tan Soeij Tjoe acted as a unlimited joint debtor for his younger brother without any right of recovery or splitting could indicate that the latter acted as “jackstraw” for Tan Soeij Tjoe (head of the extended Tan family).

So the entire theater was the concern of Tan Soeij Tjoe.

Since Tan Soeij Tjoe was just a merchant; undoubtedly it was simpler for a Lieutenant China to qualify for a tea contract than for a merchant.

In 1847 Tan Soeij Tiang went bankrupt. In the inventory of Tan Soeij Tiang was the tea contract of 29 July 1843. The liquidator (Weeskamer) auctioned the contract. Bidders were B.B. Crone and Tan Goan Kee (whose proper name in our genealogy would be Tan Goan Koeij), a son of Tan Soeij Tjoe and adopted as a son by Tan Soeij Tiang.

It was said that B.B. Crone pledged to offer in such a way that the price was not increased, on the condition that when the tea contract was awarded to Tan Goan Kee, Crone, without any payment to Tan Goan Kee, would become a 50% partner in the tea contract of 29 July 1843.

Possibly Tan Goan Koeij, as his adopted father Tan Soeij Tiang, was also just a jackstraw for his biological father Tan Soeij Tjoe.

B.B. Crone was, until the tea contract was awarded to Tan Goan Koeij, 1st Customs Official at the Directors of Cultures. A very important aspect as would appear later: he and Tan Goan Koeij were associated in the same circle of friends. As was customary at the time, poorly paid civil servants were frequently asked by wealthy Peranakan Chinese families into their homes. There was not much other entertainment, especially for civil servants without families in their place of employment. Tan Goan Koeij died in 1853. Tan Soeij Tjoe had died in 1850. His son Tan Goan Pouw ( in the books on tea plantations /2,3/ sometimes wrongly misspelled as Pau, or Pauw – this was the cause of the email of Dr. De Jong). Tan Goan Pouw, was an elder brother of my great grandfather Tan Goan Piauw (See the story Tan Goan Piauw and Thung Leng Nio on this site).

On 22 January 1854 50% of the tea contract of Tan Goan Koeij was transferred by name to Tan Goan Pouw. This was approved by the Dutch Indian Government. So 50% of the tea contract would belong to the Tan Soeij Tjoe branch again not only economical but also legally.

Alas, according to the High Government in the Netherlands this approval was not in accordance with the law:

Following Stbl.1856 no. 64 tea contracts were to be undertaken solely with Europeans and with Europeans equated (this was to protect European planters from competition with non-Europeans, thus also from “inlanders” and “Oosterse vreemdelingen”).

The registration of Tan Goan Pouw as partner co-contractor of Crone was a new contract for the remaining period of the old contract, which was contrary to the law and thus invalid.

The Chinese Tan Goan Pouw as Oosterse vreemdeling could never be a partner co-contractor of Crone because he was not equated with Europeans.

When the tea contract of 1843 had to be adjusted because of legal commercializing of all tea contracts, this was regarded as a new contract and B.B. Crone was the only contractor on the contract. Tan Goan Pouw who had paid for all of the investments in this project from his own capital had lost (legally) with one pen stroke all his investments and was dependent on the honesty of (luckily for him) the friend of the family, B.B. Crone. Economically Tan Goan Pouw was still a silent partner for Crone, and thus legally invisible!

The Dutch Indian Government was clearly aware of this “it was for Tan Goan Pouw not that important that he was no more mentioned in the tea contract, because he retained his permit to stay on the tea estate” (This would otherwise not be possible for a Chinese under the then ruling PASSENSTELSEL to live outside the Chinese camp. Tan Goan Pouw gained this permit possibly as renter/hidden silent partner of Crone).

From notes of my aunt Non = Tan Tjing Nio, daughter of Tan Tjoen Keng, grandchild of Tan Goan Piauw, we guess that Tan Goan Pouw had lived on Sinagar. This is confirmed by Mr. J.A. v.d. Chijs (/3/ p.177).

Crone has prolonged the tea contract in 1863 with Tan Goan Pouw as renter/silent partner.

On 22-1-1856 a fierce fire raged on the tea estate of Sinagar, extinguishing was not possible. The estate belongs to Mr. B.B. Crone, who let it out however to the Chinese Tan Goan Pouw and he incurred the important damage of ca f.150.000 being about 50.000 and 60.000 pounds of tea, which was ready for inspection, as well as 60 tjaings padie was burnt. |

E.J. Kerkhoven is appointed as administrator on behalf of his family. After Albert Holle deceased in 1885, E.J. Kerkhoven is appointed director of Sinagar [/4/ p.142]

This is where the book “Tea lords” by Hella Haase begins.

Epilogue

This story is a good illustration of how one can obtain information on hidden family matters by just placing your family tree on internet. We thank Dr. J.J.P. de Jong who made us aware of the tea history and Tan Eng Swie who found further information in his archive and helped to finish the search for the missing puzzle pieces.

On the website of the Tea-family-archive is a photo of the old mother Tan Goey (or Gwie) La Nio.

Apart from that she is mentioned as the “njai” of E.J. Kerkhoven, little is known about this woman. The only thing mentioned is that she was from the Chinese camp behind the house of the administrator.

Was she belonging for instance to the family of Tan Goan Pouw ? we do not know.

References

/1/ Hella S. Haasse; "De Heren van de Thee"; Querido, 2002.

/2/ Cohen Stuart; “Gedenkboek der Nederlandsch Indische Theecultuur”.

/3/ Chijs, mr. J.A. v.d.; "Geschiedenis van de Gouvernements Thee-Cultuur op Java", Mart. Nijhof, 1908.

/4/ Marga C. Kerkhoven; Eduard Julius Kerkhoven 20 Indische brieven 1860-1863; Theefamilie archief 2010.

/5/ mr. Eng-Swie TAN, “Mijn Roots (deel 3), HUA YI MAGAZINE, JRG. 28-nr.1, maart 2015.

/6/ Het Thee familie archief op : http://www.theefamiliearchief.nl/

/7/ Thee contract Tan Soeij Tiang

S.Y. Kan, Berkel,

Updated May 2018

Dit artikel is eerder in verkorte versie gepubliceerd op www.CIHC.nl

terug naar begin |